Once upon a time there were Three Billy Goats Gruff. They wanted to go over the bridge to the other side of the canal to get to the diner that sold some great grassburgers . The first billy goat, the littlest one went trip- trap- trip- trap over the swing bridge.

This script was written and performed by some of my kindergarten students about 14 years ago. We were immersed in a bridge study and had recently visited the three movable bridges that spanned the nearby Gowanus Canal. We also read lots of traditional folk tales that year. Both studies worked their way into this wonderful play that a group of the children wrote during Choice Time. The entire class acted it out for their families during our end of year celebration.

As I reflect on this whimsical production, my mind wanders to the new Common Core Learning Standards and the anxiety that I encounter around these standards when I consult in various New York City schools. I’m not about to defend the Common Core Standards. I really do believe that we can have high standards for our students without having some outside “educators” micromanage every learning point that we are responsible for teaching. However, I do think that we can interpret many of these standards in ways that make sense for young children.

Here are some ideas that I have for implementing a kindergarten folktale study that isn’t planned specifically to address the Common Core Learning Standards but that seems to meet them anyway. This isn’t a checklist of how to do a folktale study and it’s not a teacher’s script. I’m just describing some of the possibilities. The beauty of teaching is often in the excitement of that serendipitous moment when children become intrigued with some part of a story and the teacher and class take time to dig in for a deep exploration. Allowing for, and even encouraging, detours that are driven by a child’s question or observation, are so fundamentally important to creating a vital learning environment. I’ve outlined some possibilities for planning a folktale study but don’t’ forget to listen to the children and enjoy revisiting these tales through their fresh eyesight and youthful innocence.

The Common Core Learning Standards

A Folktale study will address many of the kindergarten common core learning standards for literature. Here are some of the Common Core Learning Standards that might be met by implementing a folktale study:

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to ask and answer questions about key details in a text

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to retell familiar stories, including key details and also identify character, settings, and major events in a story,

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to ask and answer questions about unknown words in a text

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to recognize common types of texts (e.g. storybooks and poems)

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to actively engage in group reading activities with purpose and understanding.

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will be able to describe the relationship between illustrations and the story in which they appear (e.g., what moment in a story an illustration depicts)

• With prompting and support from the teacher, children will have opportunities to compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in familiar stories.

Some rationales for teaching a folktale study early in the kindergarten school year

A folktale study:

• Introduces young children to the joys of traditional children’s literature

• Helps children develop a rich vocabulary

• Helps build an inviting, appropriate classroom library.

• Provides opportunities for meaningful discussions

• Encourages children to extend their understanding of literature through art, music, drama and play.

Introducing a study of The Three Little Pigs

• The teacher reads many versions of The Three Little Pigs over the course of one or more weeks

• Posing open-ended questions that encourage children to synthesize the ideas in the book and theorize on possible outcomes facilitates discussions. For example:

-How might you have built your house if you were one of the pigs and you wanted to protect yourself against the wolf?

-Why would you build it that way?

-What do you think it means when we describe someone as clever? (This might not be a word that children are familiar with and could involve some defining by the teacher after children have a go at figuring it out)

-Have you noticed any examples of clever thinking on the part of the pigs or the wolf in the story?

– Why do you think the mother pig sent the little pigs out into the world by themselves?

-How do you think the little pigs felt about leaving home?

• Children can be encouraged to make connections to incidents in their own lives and in other stories by referring to the pictures in the text for support. When children see the pigs hiding in fright from the wolf behind the door, it could open up a discussion of times when they were frightened and how they handled their fright. When the pigs trick the wolf into going apple picking at the wrong time, it might remind children of tricks that they played on friends or siblings. On the other hand, it might also begin a conversation about times that they, too, went apple picking! Straying from the story plot and remembering a family trip to an apple orchard could be a fairly typical connection for a five-year old to make in response to the apple-picking illustration.

Class Discussion

The teacher’s line of questioning determines the quality of the discussion.

• Initially, simple factual questions might be asked such as, “ What did the three pigs use to build their homes?”

• After asking simple questions, more thought-provoking inquiries could be asked such as “I wonder why the wolf was so easily fooled by the pigs?”

When open-ended questions are posed, the teacher does not expect children to arrive at one definitive answer. A key point here is that all theories are debatable and worthy of discussion. This supports higher-level thinking and richness of language. Open-ended questions can tap into children’s curiosity, sense of wonder and ability to attempt some creative thinking. When the teacher asks open-ended questions, children are presented with a message that says, “I trust you to have good ideas and I value your thoughts.”

Drama and Play

All of these supports inspire children to interact with the text using age-appropriate modes of exploration.

• The teacher can encourage children to refer to illustrations when they are reconstructing the story as they play in the various Choice Time centers. This can be done by adding copies of the book to the dramatic play center and to the block center. A book may also be put in the art center.

• Photocopies of illustrations from the book can also be posted in easy view in these centers too.

• Teachers can make story props available. Small models of animals from the story can be put in the block center.

After hearing many versions of the same folktale

• The class could create a Venn diagram, showing similarities and differences in the various versions of the story. For example, there are always three pigs but perhaps in one story, instead of going to pick apples, they go to pick cherries!

• Children might create personal versions of the story in their writing workshop. Four and five year olds would probably begin with drawings. Children could dictate the text to the teacher, or if they are ready to use invented spelling they could write it themselves.

• These new versions could first be displayed on a bulletin board in the classroom and later turned into class books.

• The teacher could document this writing process by photographing children working on their books and recording brief transcripts of children’s thoughts and comments as they work.

• These photos and children’s comments could be added to the wall display, which would serve as a visible assessment of the learning process.

• At independent and partner reading, children should have time to “reread” the books to each other. At this stage in their literacy development, they will probably be retelling the story using picture clues and the memory of having heard the book read aloud.

• As children read, the teacher sits at the side of a child to engage the student in a book discussion.

• These one-on-one discussions give the teacher the opportunity to hear if the child is using storybook language, following the sequence of the story, speaking in complete sentences and remembering significant expressions from the story (i.e “not by the hair of my chinney chin chin”).

• These conferences provide the teacher with invaluable information for future lesson planning and for differentiating instruction.

• If there is a big book version of the story, this can be used for shared reading.

• A small copy of a folktale book can be used for shared reading by projecting the book onto the wall or Smartboard. If the school does not have a document projector, an overhead projector can be used with transparencies of each page.

• Shared reading gives children opportunities to ask and answer questions about key details in the text, retell this familiar story, including key details and identify character, settings, and major events in the story, with the support of the group.

• Shared reading scaffolds the retelling and reenacting of the story that will take place during Choice Time and independent reading.

• For kindergarten children, singing is a joyful and crucial part of their school experience.

• The class might compose a Three Little Pigs song, using a popular tune or by making up an original tune!

• The teacher could act as scribe, recording the words to the song.

• This class-composed song could become one of the songs that would be sung throughout the year!

• After children know the song “by heart” the song chart can be used for shared reading as they sing along.

• Reciting poetry can be another way to make connections to the story.

• Young children have for generations recited Mother Goose poems. To Market, To Market could first be learned as a playful chant. As children learn the poem the teacher can help them understand some of the unfamiliar vocabulary such as “hog” and “jig”. (The children might also try dancing a jig to some appropriate music!)

• What was first learned as a chant can now be transferred to a shared reading chart. Because children know the poem “by heart”, they will be ready to make connections to some of the significant words that are written on the chart.

To market, to market

To buy a fat pig;

Home again, home again,

Dancing a jig.

To market, to market

To buy a fat hog;

Home again, home again,

Jiggety-jog.

• In a shared writing experience, children might dictate a new class version of a folktale (or create an entirely new tale, using the folktale format!).

• Individual groups of children can illustrate each page of the new version of the folktale that the class created, matching their drawing to the words on the page. When these pages are completed, the class will have an original Big Book version of the story. This version can be revisited many times for shared reading and dramatic presentations.

• Informational texts that match the story can be read to the children.

• During a study of The Three Pigs, the teacher might read Gail Gibbons’ informative text, Pigs.

• Children could be encouraged to make connections between the attributes of real pigs compared to the pigs in the folktale.

• Some other nonfiction books to read might be “Pigs! Learn About Pigs And Learn To Read – The Learning Club!” and Pigs (First Step Nonfiction Farm Animals) by Robin Nelson

• The introduction of a new folk tale such as The Three Billy Goats Gruff could follow up the study of The Three Pigs.

• Reading a variety of folktales provide a perfect opportunity for comparing and contrasting adventures and experiences of different characters.

• The Three Pigs and the Three Billy Goats Gruff all had to use their creative intelligence to overcome obstacles. How might you describe the similarities and differences in these obstacles? Did you notice any similarities or contrasts in the ways that the bad guys in both stories were outsmarted? The possibilities for discussion are endless!

• Because of all the opportunities for comparisons to be made between the two tales, the conversation would most likely become even more complex than proposed by the Common Core Standards!

“Helping children engage in the drama of reading, helping them become dramatist (rewriter of the text), even critic (commentator and explicator and scholarly student of the text), is how I think of our work as teachers of reading.”

Aidan Chambers

Tell Me: Children Reading and Talk

“Teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit.”

John Steinbeck

Five years ago, Dana Roth a marvelous kindergarten teacher at P.S. 10 in Brooklyn, came to my home to work on writing a chapter for Teaching Kindergarten: Learning-Centered Classrooms for the 21st Century with me. When we took a break in our writing, Dana asked me for some advice. The children in her class were particularly interested in airports and airplanes. She wanted to begin an inquiry project with them but she knew that it would, because of security rules, be impossible to make a class trip to the airport. Should she just see if there was something else that interested the children? I suggested that we put our heads together and create an anticipatory web. That might give her some direction to see if an airport/airplane investigation would make sense. This is what we came up with:

Five years ago, Dana Roth a marvelous kindergarten teacher at P.S. 10 in Brooklyn, came to my home to work on writing a chapter for Teaching Kindergarten: Learning-Centered Classrooms for the 21st Century with me. When we took a break in our writing, Dana asked me for some advice. The children in her class were particularly interested in airports and airplanes. She wanted to begin an inquiry project with them but she knew that it would, because of security rules, be impossible to make a class trip to the airport. Should she just see if there was something else that interested the children? I suggested that we put our heads together and create an anticipatory web. That might give her some direction to see if an airport/airplane investigation would make sense. This is what we came up with:

The class took a trip to the Saker Aviation Heliport but first they made a list of questions.

The class took a trip to the Saker Aviation Heliport but first they made a list of questions.

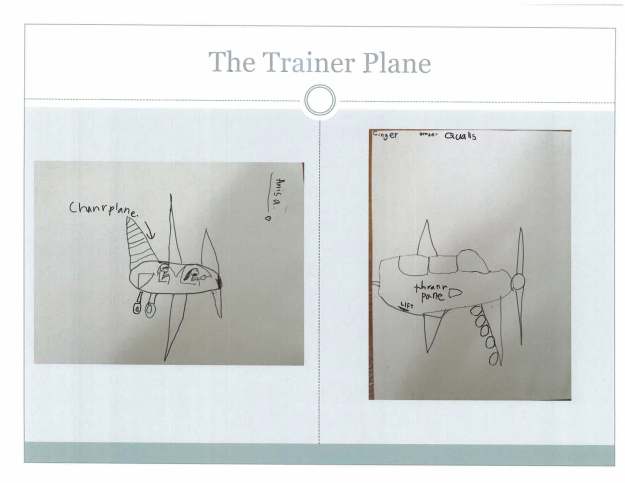

Back in class…

Back in class…

I

I