A group of educators recently decided to meet on Zoom to discuss what we could do about the disturbing direction of Early Childhood education in the New York City public schools. Years that should be filled with opportunities for exploration, inquiry, social interaction and play have turned into days filled with scripted, direct instruction. This leaves very little, and in many cases, no, opportunities for joyful, engaged learning and informative, insightful and fulfilling teaching. We have composed a proposal that we will present to Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani and to his eduction transition team.

Ideally, we would like our proposal to be circulated as widely as possible. To this end, we hope that you will share it with anyone who is particularly concerned with the education of children, 4 to 8 years old.

We would also love to have your feedback.

Here is who we are .

Anna Allanbrook (retired principal, The Brooklyn New School)

Nancy Cardwell Ph.D (faculty member, Graduate Program in Early Childhood Education, School of Education , The City College of New York)

Renee Dinnerstein (Early Childhood Literacy Consultant)

Beverly Falk Ed.D (director, the High-Quality Early Learning Project and Professor/Director Emerita, Graduate Program in Early Childhood Education , The School of Education, The City College of New York)

Deborah Meier, (founder and retired director , Central Park East schools)

Lauren Monaco (early childhood educator and activist)

Gil Schmerler, Ed.D ( retired director. Leadership for Educational Change, Bank Street College of Education)

Our proposal

We are a group of NYC educators – founders/principals of learner-centered schools, faculty of the City College School of Education and Bank Street College of Education, and teacher/parent activists for learner-centered education. We write to share some of our thoughts/concerns/recommendations for the NYC Public Schools that we hope the Mamdani administration will consider and put into action. While there are many structural/budgetary issues that need to be addressed, we are especially concerned with early childhood education and will focus on this – our area of experience/expertise. What follows are some of our concerns with recommendations for how to address them.

1. We believe that the NYC Public Schools (NYCPS) view of early childhood is too narrow.

Currently, early childhood – and the central administrative team overseeing it – considers early childhood to be birth – 4. The nationally recognized professional standard and developmentally-based age range for early childhood is birth – age 8. It is widely accepted in the fields of education, medicine, psychology and neuroscience that during the first 8 years of life optimal development is supported by active learning/play where children have extensive periods for choice and inquiry facilitated by teachers’ responsiveness to children’s questions, interests, and understandings. Young children learn through active involvement with materials and relationships with children and adults. Unfortunately, in too many classrooms there are no opportunities for this: no choice/work time, no materials with which to engage in educative play. Kindergartens throughout the NYC Public Schools do not have choice/work centers, blocks, dramatic play areas, trips, and/or recess. Work sheets and didactic teaching dominate the day, with brief periods of ‘playtime’ given as a reward at the end of the day. The absence of educative play opportunities in kindergarten through 2nd grade is resulting in increased incidences of anxiety and depression. Some pediatricians have noticed a significant enough pattern to call this ‘play deprivation’.

We recommend instead:

– Align the NYCPS early childhood definition with national, professional, and global standards, birth to age 8 years, specifically to include kindergarten through 2nd grade.

– Give responsibility for young children’s learning in K-2 to the NYCPS early childhood team.

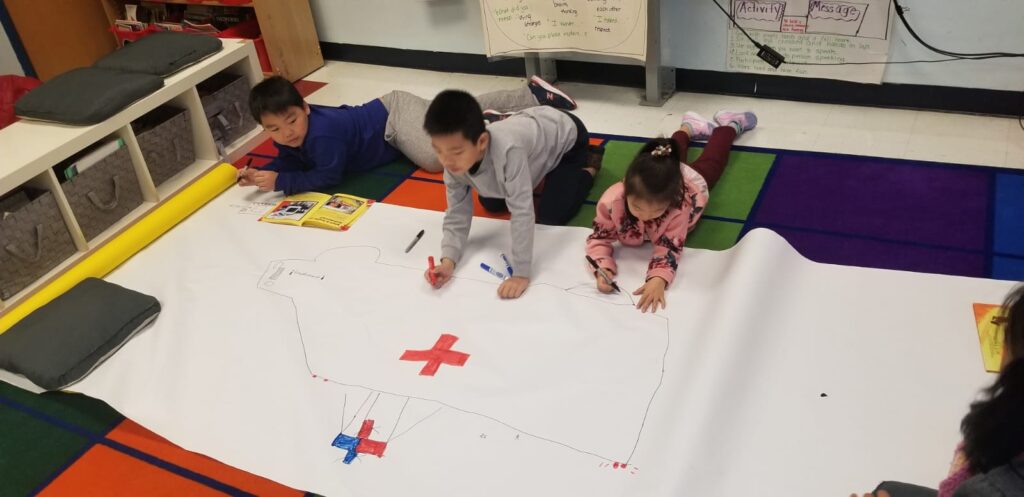

– Ensure that choice/work time be a prominent part of every early childhood classroom where children can make choices, engage in inquiry.

– Ensure early childhood classrooms be amply provisioned with materials for active learning, including (but not limited to) blocks, manipulative materials, dramatic play equipment, books, and art supplies.

– Ensure all children have at least an hour of outdoor play/recess each day

2. We are concerned about the damaging effects of the mandated, scripted curricula implemented in all grade levels.

Developmental and neuroscience research have established the importance of educators’ responsiveness to children’s interests, questions, cultural and linguistic backgrounds. A scripted curriculum does not allow opportunities for the “serve and return” exchanges that neuroscientists point to as critical for optimal brain development. Further, the scripted, generic curriculum doesn’t provide the necessary responsiveness to the diversity of children’s and families’ backgrounds, because the mandated, scripted curriculum does not connect to the children’s backgrounds/contexts/languages. Children and teachers are required to be passive recipients of external forces, rather than dynamic and active participants in their learning as promoted by neuroscientists, psychologists, and pediatricians. Additionally, millions of dollars are being spent on purchasing and enforcing use of these curricula that could be better spent in ways we suggest below.

We recommend instead:

– Center curriculum development around national/state/district/professional standards, for example, those of the National Association for the Education of Young Children

(NAEYC).

– Collaborate with community-based teachers’ and parents’ groups to choose/shape/develop their own curricula that is relevant/connected to the contexts of children’s lives.

– All curricula should be mapped to demonstrate the coverage and alignment with national/state/district/professional standards.

– Offer ongoing, substantive professional development to support educators’ content and pedagogical knowledge to sustain young children’s learning and optimal development.

And/or

– Offer pre-developed curricula, as guides, that integrate young children’s diversity of experiences/languages/cultures, making it clear that the curricula are guides, not mandates.

– Offer ongoing professional development to assist educators in how to be responsive to children’s interests, questions, different strengths and modes of inquiry, cultural/racial/linguistic backgrounds

– Provide active learning/play-based environments that will develop young children’s academic skills, content knowledge, social emotional learning and critical thinking skills to help them distinguish between facts and misinformation.

– Provide time in the school day for young children to exchange ideas, learn to listen to and be respectful of others, and reposition children as well as the teacher as resources for learning in the classroom.

– Provide time for conversations and relationships in the classroom to support the development of empathy and understanding toward others that are critical to learn about and sustain a democratic community in the classroom in preparation for life-long, active civic engagement. For example, in Denmark all children aged 6-16 years have a period in their school day focused on the development of empathy toward others. This contributes to the fact that they are ranked internationally as the happiest society in the world.

3. We are concerned about the reading programs that do not reflect the consensus research from developmental psychologists and neuroscientists about how children learn to read.

We are further concerned about the lengthy periods of time spent on worksheets, passive instruction on phonics, phonemic awareness, and decontextualized skills at the expense of meaning making and other elements of literacy development. Neuroscience advocates for a dual focus on meaning-making elements (content and experience-based knowledge, children’s interests, culture/linguistic backgrounds) in addition to decoding elements (phonics, phonemic awareness, alphabet knowledge etc. See chart below.

We recommend instead:

– Expand the notion of reading development beyond phonics by adding the extensive rich supply of children’s literature to skill instruction in order to capture children’s interests and excitement that has been proven to enhance the literacy learning process.

– Infuse literacy learning into active, project-based learning experiences across all content areas, both fiction and non-fiction. We also urge the use of ‘functional literacy development’ that includes making signs in the block area, writing lists, letters, and labels in dramatic play areas, using charts to document children’s comments, questions, ideas and understandings, and pointing out awareness of environmental print, etc.

4. We are concerned about the overuse of testing that does not support children’s learning and that consumes inordinate amounts of educators’ time.

We recommend instead:

– Encourage and support educators’ use of professional development standards-based performance assessments and multiple forms of data collections mapped to standards. This can include portfolio collections of children’s work, documented observations, and the use of developmental continua mapped to professional, national, state, and district standards. This approach was developed in NYS in the 1990s and early 2000’s and has data to back up its efficacy.

5. We are concerned about the overuse of screens and artificial intelligence in schools.

Developmental and neuroscience psychologists along with pediatricians warn against screen time for children, especially young children under 9 years old. Neural connections that are the brain structures that support learning are consolidated quickly and effectively with ‘serve and return’ relational and in real-life interactions rather than through abstracted online/digital encounters. Additionally, artificial intelligence can be deceptive and keep children from developing the social emotional and relational intelligence necessary for sustained relationships throughout the lifespan as well as developing the skills they need to be critical thinkers and distinguish reality from misinformation.

We recommend instead:

– Limit screen time and the use of artificial intelligence to encourage real-life, in-person interactions that support learners to learn how to be critical thinkers and to distinguish fact from fiction. Limiting screen time is an important support to help children develop social emotional learning to support interactive and project learning.

– Provide ongoing professional development to help educators develop ways to harness technology in developmentally supportive ways to nurture healthy brain development and learning.

6. We are concerned that large numbers of children and families in NYC schools are unhoused, suffer from food insecurity, and/or are in need of comprehensive supports to survive.

Additionally, we see a need for schools to attend to the voices and concerns of parents/families/caregivers in the community and involve them in the learning life of the school.

We recommend:

– Reintroduce the community school model that utilizes the resources of community-based organization such as the Children’s Aid Society to provide the necessary supports like access to food, housing, health screening, vaccines, dental care, hearing exams, eye exams all critical for children’s academic success.

– Create collaborative governance structures that give voice to parents/families/caregivers/community concerns in decisions about the education of their children.

Respectfully submitted (in alphabetical order):

Anna Allanbrook, retired principal, the Brooklyn New School

Nancy Cardwell, Ph.D., faculty member, Graduate Program in Early Childhood Education, School of Education, The City College of New York

Renee Dinnerstein, early childhood literacy consultant

Beverly Falk, Ed.D., director, The High-Quality Early Learning Project and Professor/Director Emerita, Graduate Program in Early Childhood

Education, The School of Education, The City College of New York

Deborah Meier, founder and retired director, Central Park East Schools

Lauren Monaco, early childhood educator and activist

Gil Schmerler, Ed.D., retired director, Leadership for Educational Change, Bank Street College of Education

On Tuesday, September 6th the

On Tuesday, September 6th the On Tuesday, September 6th the

On Tuesday, September 6th the